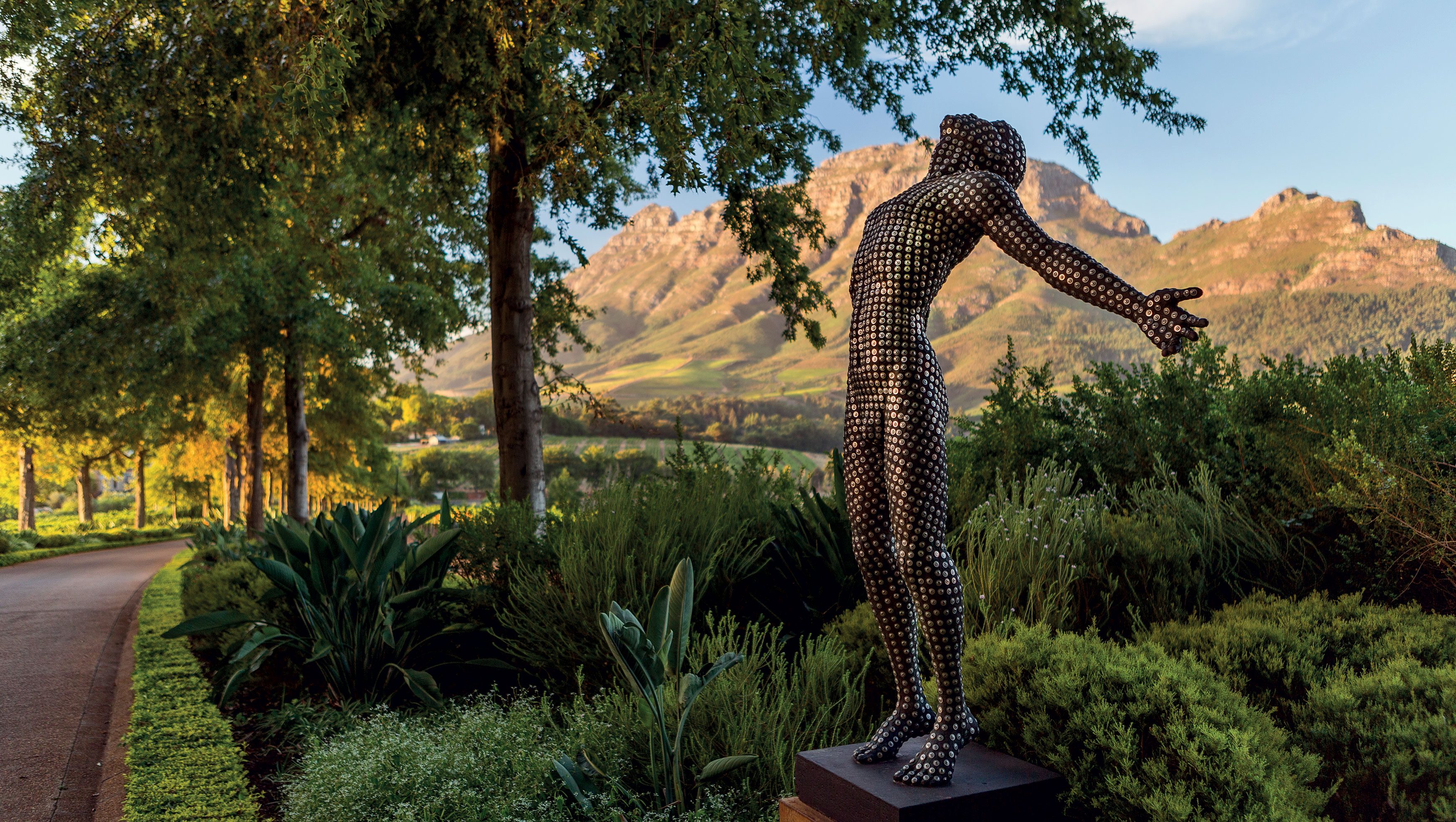

Simon van der Stel took over from Riebeeck as Commander of the Cape in 1679 and explored beyond the confines of coastal Cape Town, heading deeper into the great Floral Kingdom, where the fragranced and biodiverse Cape Flats promised greater prospects for cultivation. Vines were planted towards the hills of Constantia, over Table Mountain, and eventually made their way to the fertile valley of Stellenbosch. The rich soils, protected climate and higher lands were paradise found for viticulture, and Stellenbosch – named after its intrepid founder – remains at the heart of the African wine industry today.

Van der Stel was also smart enough to bring the Huguenots, fleeing from their own winelands in France, to the highlands of Stellenbosch in the late 1680s. They brought with them French wine expertise and knowledge, establishing the sub-region of Franschhoek – ‘French Corner’ – where the verifiably quaffable wines lent prestige to a growing industry.

Although wine production had flourished with relative ease, transporting the wines from Franschhoek to Cape Town’s harbour required a four-day, often hazardous journey crossing two particularly frightful passes. The first, Helshoogte Pass, translates to ‘Hell’s Heights’ because the 7km route winds around sheer drops and steep mountain faces – bends that could prove fatal for traders or their cargo-laden wagons. That pass was followed by Banghoek or De Bange Hoek, the ‘Scary Corner’. The heights were hairy, but its moniker actually came from the revealing vantage point where you could instantly see the resident herds of elephants, prides of lions, crashes of rhinoceroses, leaps of leopards and gangs of buffalos that lay in the valley ahead. At the turn of ‘Scary Corner’, you knew what fate awaited you, for better or worse.

In spite of frequent perils, the first pioneers succeeded. They gave seed to a wine industry that would not only keep the sailors happy and the scurvy at bay, but also outlive the original medical mission and create a legacy leading to something far more noble.